Blog

Press Release: July 24, 2013

I want to go to the puu by Chris Laboube

Living in Ghana—or any foreign country outside your home country—requires some form of communication. The most effective way of slowly bridging the vast communication gully between the words you use and the words the nationals use is for you—the foreigner—to learn the local or regional or national language.

This is the correct thing to do, but does not answer my question as to what the man was trying to say to me. Learning the local, regional or national language may not be easy—an excuse I hear often from fellow Americans and Canadians—though certainly quiet possible.

God gave us a brain that can create and process so much information, surely we could at least give ourselves a little credit and think that we can learn to speak a foreign language.

Once you begin learning to communicate—even minimally—in a foreign language, you have created a breach in the linguistic barrier which will only widen if you keep at your studies. This will lead you to communicating much more than when you first arrived and possibly even becoming fluent.

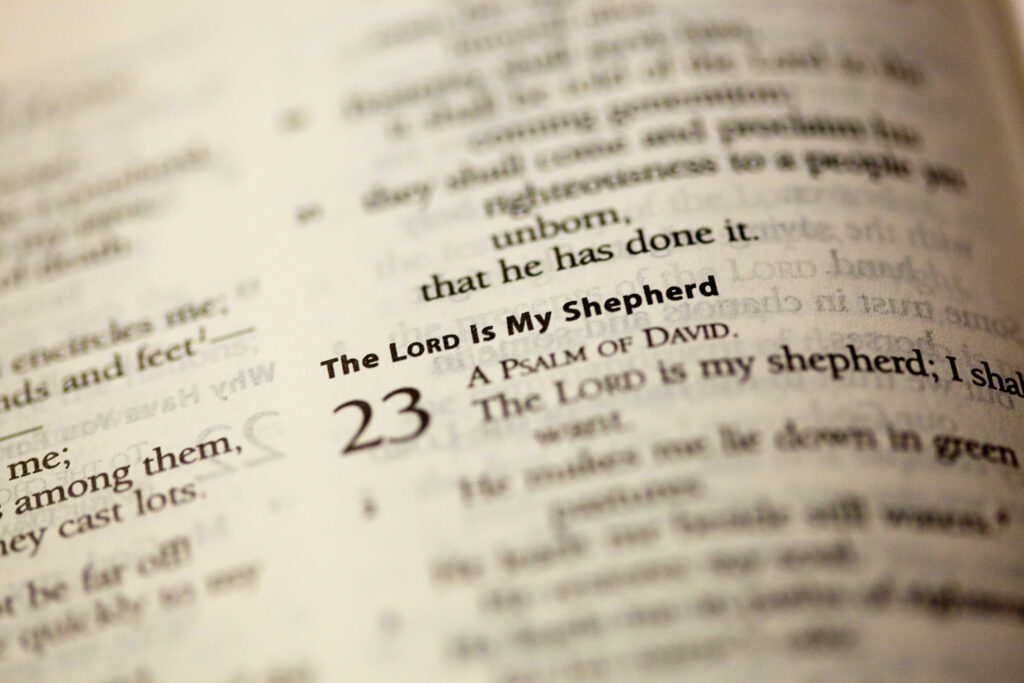

“And Jesus said to the father, ‘If you can’! All things are possible for one who believes.” (Mark 9.23)

I have been studying Dagbani for a lot of my time here in northern Ghana, and honestly my language ability is still pretty minimal. I can greet people, ask about their health and well-being, their family, etc. I can ask the price of fruit and vegetables in the market. And then I usually have exhausted my very limited Dagbani ability.

And even though I can’t carry on full sentences with in-depth thoughts, I still enjoy meeting people and trying to communicate. Plus, Ghanaians generally seem quite receptive when the tall white guy comes around to buy fruit and stumbles around with a few Dagbani words. Some Ghanaians will correct my Dagbani, helping me along the way.

Often conversations fall into English when the Ghanaian realizes that I have used up all my Dagbani. But not all Ghanaians speak English, or speak it well enough to explain things to me.

Take the old woman who lives next door to me. I have greeted her and the people at her house many times when I walk or drive past her house. (I live on a dead-end street.)

One day I was out walking I saw her hobbling up ahead. She looked like she was on a mission. Maybe she was just walking to the nearby mosque. I don’t’ know. We exchanged a couple of regular greetings and then I thought we were finished and I picked up my pace.

Then she threw another question at me and I had no idea what she said. Trying to be polite, I turned around and used the universal “hmmm?” so she could repeat what she just asked me.

Out comes the question again. I had no idea. I was lost and felt a little embarrassed because I didn’t want to disrespect her by just turning around and running away from her. (Ghanaians respect old people very highly). She pinched her right fingers together (like she was putting food into her mouth) and then touched her mouth and said a word that sounded familiar, but was struggling to understand.

I thought she was asking for sugar, but honestly did not know. I mumbled something and shook my head and then held out both my hands to indicate that I did not have anything. Then I think I even said softly “I don’t’ know.” I smiled as apologetically as I could and then I turned and hurried on my way trying to look like I, too, was on a mission as she obviously was.

I felt bad not know what she asked me, but knew that her family and friends would come to her rescue soon and get her whatever she was asking for. Her family and friends nearby come and cook for her and take care of her and her house.

This probably happens more often than I realize, and it just reminds me the importance of communicating. Of course, just because I don’t know how to speak Dagbani fluently doesn’t mean that communication doesn’t happen.

My day watchman is an excellent example of this. He and I make an odd pair. His English is probably just a little more than my very limited Dagbani ability, and yet we manage to make it through each day.

Every so often, when his work at my place is done, the day watchman asks to go work on his small plot of land that he calls his “farm” which is just about a five-minute walk from my house. You can see his “farm” from my front gate.

This is what he says: “N chaη la farm.” [I want to go to the farm.] My watchman assumed that I don’t the word for “farm,” which in Dagbani is “puu.”

I say, “OK, you can go to the farm” [in Dagbani: “Toɔ, a chaη la puu.”] Though the last time we had a similar exchange, I did the same thing that my day watchman does and I said: “Toɔ, a chaη la farm.” [OK, you can go to the farm.] I didn’t realize what I had said until a little later and then I laughed at my mistake.

And then I thought that’s how communication works. Language is not static. Sure, there are rules and standards of how to use languages, but communication is about two people trying to share ideas in a foreign language. So what if I mix an English word in with my Dagbani now and then? If I accomplished what I set out to do in my communication, then I was a success whether or not I truly understood what was said to me. Plus, it makes communicating much more interesting!

Rev. Chris Laboube has a Scripture Engagement ministry in Ghana. To read more about his life there, visit the LaBoube Listening Post.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.