News & Media / Podcast / Carry on the Work

Carry on the Work

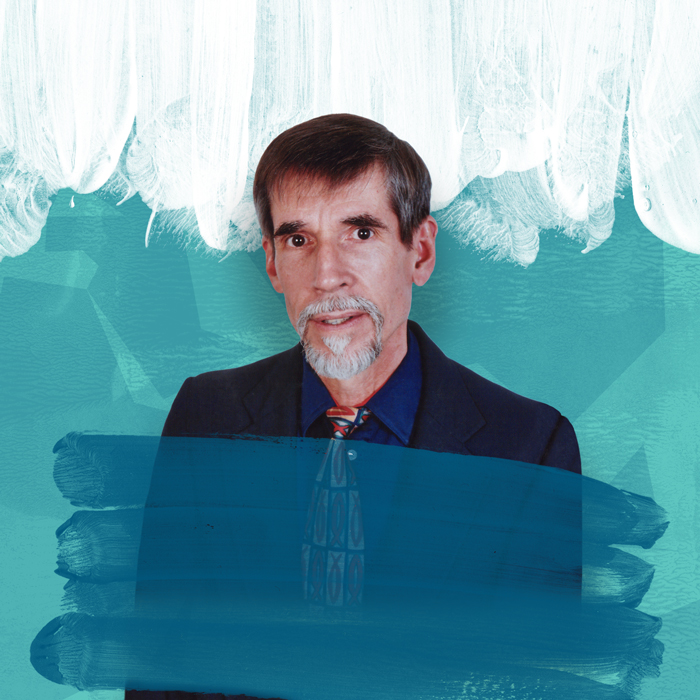

Dr. Ernst R. Wendland

About The Episode

Dr. Ernst R. Wendland served as an instructor at the Lutheran Seminary in Lusaka, Zambia, as well as a United Bible Societies Translation Consultant.

He is the author of numerous studies on the Bantu languages of South-Central Africa, biblical exegesis, literary-poetic analysis, rhetorical criticism, and translation theory and practice.

Enjoy this podcast with Dr. Wendland reflecting on a lifetime of ministry.

00:00

Dr. Ernst Wendland

The opportunity to work with national colleagues in the work to, on the one hand, teach them, but on the other hand to learn from them. The greatest joy is to see some of the things that I’ve taught them they are following up on, and now they are teaching me as they carry on the work in the different fields.

00:25

Rich Rudowske

You welcome to the essentially translatable podcast brought to you by Lutheran Bible translators. I’m rich Rudowski.

00:31

Emily Wilson

And I’m Emily Wilson.

00:32

Rich Rudowske

And we have the chance here as we continue this year to celebrate the.

00:35

Rich Rudowske

500Th anniversary of Luther’s translation of the.

00:38

Rich Rudowske

New Testament, to talk to a huge Bible translation scholar, Dr. Ernst Wenland, who has been a missionary for 50 years in Zambia, worked as a seminary professor and started a Bible translation center in Zambia and worked in a lot of different zambian languages.

00:55

Emily Wilson

So this is just one of an installment of celebrations that we have for the 500th year. And we encourage you to check all of them out at go lbt.org 500 and be able to check out what is happening in the world of Bible translation and how partners around the world are coming together with this vision for God’s word at the center of the church and how transformative it is. And Dr. Wenlin was able to share that.

01:23

Rich Rudowske

Yeah, we had him here for the Concordia Mission Institute, and then he came out in here and we talked in the studio and about a wide range of topics. So, yeah, I think that you guys are going to just enjoy hearing from Dr. Wenland, both the depth of the professional work that he’s done, but also just personally, his life of service and what the Bible means to him. So enjoy this episode with Dr. Ernst Wendland.

01:49

Rich Rudowske

So we are in the podcast studio today with Ernst Wendland, and great to have you with us today.

01:54

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Thank you.

01:54

Rich Rudowske

Before we get started here, I’d like to learn a little bit about your background. How’d you get involved in Bible translation ministry? What brought you to Africa in the first place?

02:03

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Yeah, I think we really have to begin there because in fact, it wasn’t I that came to Africa. It was my father who was called as a missionary, a Wells missionary in 1962 to start the worker training program for our mission in Northern Rhodesia at the time. So he brought the family along, that’s husband, wife and six children. So that was my first introduction to Africa. And then later on I went to school for two years in Zambia, Northern Rhodesia, and then returned, did my college work at Northwestern College. And I was sort of wondering, I wanted to get into Bible translation in some way. I had some contact, as I mentioned this morning, with LBT. But then there was an emergency call at the lutheran seminary where my father had started. They needed somebody to help teach out at the Lutheran Bible Institute.

02:56

Dr. Ernst Wendland

So I was on an emergency call then in 1968, and that sort of got me started in the teaching program. My call was extended or actually made permanent, then established, if you want, in 1971, when, after I got involved in translating church literature. So I was then called as the language coordinator for publications in 71. And that, as far as my church work goes, was how I got started in Africa. I might just add, when we talk about what brought me to Africa, I think I wanted to add one comment on that and how did I stay in Africa? What kept me in Africa?

03:36

Speaker 5

Sure.

03:36

Dr. Ernst Wendland

And I just wanted, since were talking about relationships this morning, it was a wonderfully supportive wife and family that when you last for 50 years, you’ve got to have more than just longevity and desire. You have to have that support. And I really appreciated that I had through the years.

03:54

Rich Rudowske

Yeah, that’s wonderful. By the way, do you remember your dad’s church before he took the call? This is St. Matthews, so that’s where I went to church when I was a kid, too. Is that right? Your dad was still a hero. By that I mean I started going to church there in 1982 and was confirmed there in 1987. But yes, it was still, like, everybody still talked very fondly of your dad. So, yeah, I was just curious.

04:17

Dr. Ernst Wendland

He enjoyed the ministry there. He enjoyed Life there in Benton harbor.

04:20

Rich Rudowske

Quite a place, but yeah, so that’s where I’m born and raised as well.

04:23

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Wonderful.

04:23

Rich Rudowske

Yeah. Anyways, so you started there at the seminary and you had some contact with LBT, so you had some interest in language and so forth. So how did you learn the Chichewa language? That part of your call there or something you were already doing while you were living there?

04:39

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Before I realized that to get involved in translation, I would have to learn one of the major Bantu languages and Chewa. That’s how it is known in Malawi. It’s the national language of Malawi, Chichewa. It is known as Chinyanja in Zambia. So I started with lessons that were taught by a missionary. He went through the peace Corps course and did all sorts of drills and that. So that got me started. But one of my main helps was the students at our seminary. Since Nyanja was sort of the lingua franca of Lusaka, the city there, it’s actually the capital of Zambia. The students all spoke it, and I would try to identify those who came from Malawi and sit with them, try to sit down with one of them an hour a day or so and just try to do conversation.

05:26

Dr. Ernst Wendland

So that was an important way to get from the book into actually using the language. And then I think one of the things that helped me a lot was I listened to radio programs. And not only listened, I recorded them, especially drama. Christian. Not christian drama, but secular drama stories. And that’s really what got me into my dissertation work. And then I did some field work out in the eastern province, collecting folktales. So that’s basically how I tried to learn that. You never really say you learned the language. You’re always learning the language. And I continue to try to dialogue with students when I teach them.

06:04

Rich Rudowske

So how were you trained for the Bible translation ministry then? Of course, the language learning skill is a great asset. And number of informal ways you can learn on the job if there are other ways that you train formally and informally.

06:17

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Well, as it so happened, I learned about Gene Nida, of course, when I was doing reading and Bible translation, and he happened to be offering a UBS translation workshop in Kampalo, Uganda, 1969. I wasn’t a UBS staff member or anything, but I wrote and asked if I could attend, if I paid all my fees and everything. I was accepted there. So I took a three week course there, and that introduced me to Gene Nida, who was at the time bringing out Tapa, theory and practice of translation. So that got me in on the ground floor with dynamic equivalence translation. Then later on in 1971, I took a three month SIL course in the United Kingdom, Horses Green. And that was very helpful because the instructors there were Katie Boundrell and the callos, John and Kathleen Callo. They had guest lectures.

07:13

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Ken pike was in longacre Grimes. It was just a constellation year of all the grades of SL came in that summer. And so I was introduced in that way. Then they encouraged me, actually, Gene did, to do my doctoral work. And I asked, what would you advise? He advised not to go into biblical languages. I already had undergraduate work in that. He said, if you’re going to do translation work in Africa, there’s one place that recommend, and that was at the University of Wisconsin, which offered the department of African Languages and Literature. He said, get a doctorate there. Wow, that’ll really help you. And Phil Noss was there, and he was my advisor, so that was a great help. I was there for 74 to 79, working on a doctorate there.

08:00

Rich Rudowske

All right, so then you worked as a United Bible society’s translation consultant. We’ve talked on our podcast before about translation consultancy, but maybe just really briefly describe what a translation consultant does.

08:14

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Well, a UBS translation consultant was responsible for managing the translation program on the ground in the different parts of Africa. Jacob Lowen was my predecessor. He was there from 70, 71 to 74. And I sort of served as his ta. And we’d visit different projects, encourage him, some project we’d be starting at the particular time were producing. Dynamic equivalence, translations, translators, reviewers, and so forth. Just all general, all around management work that you do to keep these projects going and to ensure quality control.

08:56

Rich Rudowske

Okay. And so, yeah, what, I guess, geographic area or how many projects did you do? What did that look like in terms of your assignment and the scope of it?

09:06

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Okay, well, when I took over from Jake, first, as an honorary, I did my work, I should mention pro bono, that is, I wasn’t getting two salaries. I sort of put it together with my teaching work, and Wells allowed me to do that. So I established the Lusaka translation center on the campus of the school. They gave me a room there, and we worked on about a dozen full Bible revisions and new translations over the years. So I had a manuscript examiner and a keyboarder there in the office.

09:43

Rich Rudowske

All right. And so this was then done, as you’re saying, in conjunction with your work, your primary, if you will, I guess, work, was an instructor at Lusaka Lutheran seminary. How did that all fit together?

09:53

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Yeah, it was a sort of challenge at times to try to balance all the balls in the different jobs that I had to do there. But it was actually mutually beneficial, because the seminary students that I had often could help me in checking a different translation of a different language. I say tonga as opposed to Jnanja. So they helped me in that way. And when I would work with Bible translation teams, then I’d be working with different students at different levels. And they helped me to become a better teacher, I think. So. I think that the two types of work really complement one another, if you want to put it that way.

10:31

Rich Rudowske

Yeah, definitely. So it is a great situation if the church has the idea of Bible ministry and the importance of Bible translation as a key component of what they’re doing at some point, educational and even in my world now, as a Bible translation organization administrator, I mean, that’s what we’re striving for, is to have the church have Bible translation and scripture engagement as a central part of mission. So it’s pretty unique that for decades, that’s, in some small sense, what you were doing.

11:01

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Well, I must give credit to Wells. I don’t think were involved in any other Bible translation, except some of the seminary profs did work on the NIV. But to be actually involved in on the ground Bible translation work that they allowed me to do, that was a credit to them.

11:18

Rich Rudowske

So you’ve been talking some. You mentioned about dynamic equivalence. So let’s talk a little bit about translation styles and sort of define for the listeners what these different styles are. And in the english speaking world, what Bible sort of looks like that style, I guess. So, dynamic equivalence. Well, let’s see. That’s the best way, I guess.

11:38

Speaker 5

There’s sort of a range.

11:39

Rich Rudowske

So how would you like to go about talking about it?

11:41

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Okay. Yeah. Let’s start with formal correspondence translation. An example would be the ESV or NRSV. This is a translation type that seeks to reproduce in the target language as many lexical and grammatical forms of the biblical text as possible. It aims to give the reader a picture of the recorded linguistic features of the Old Testament or New Testament, sometimes called literal translation. A functional equivalence version, then also earlier called dynamic equivalence, is exemplified by the GNB good News Bible, or the new literary translation. This is a translation that seeks to convey the semantic content as well as some of dynamic impact and appeal of the biblical text.

12:30

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Now, to do this, often the original lexical and grammatical forms of the biblical text have to be changed in order to accomplish this, to communicate the main functions of the biblical text, whether to give information to express the feelings of the speaker, or to affect the audience in a natural way. This is sometimes also called a meaning based version. Then we might have what I term medial equivalence, what we have in the NIV new international version, a translation that varies between formal correspondence and functional equivalence, sometimes retaining the original forms where they are deemed important, but more often changing those forms that are considered too difficult or unclear if rendered literally. Then there’s a fourth type called I call a paraphrase. This is a translation that seeks to be very meaningful, colloquial, and up to date in the target language, in English or whatever.

13:28

Dr. Ernst Wendland

It thus feels freer to change or domesticate the forms and sometimes also the content of the biblical text, much more so than in a functional equivalence version. For example, an example would be the voice translation, where Yahweh of the Old Testament is translated as the eternal, and the word referring to Christ is translated as the voice. Another example of a paraphrase would be the psalm songs that my students prepare when they do a version of text that they do have an exegesis of and then prepare as a song again.

14:04

Rich Rudowske

I’m going to go off our script a little bit. But of those types of translation, the formal equivalents, dynamic equivalents, without getting too far into it, sometimes there are folks that really say it has to be one or the other, or one is better than the other. If somebody comes to you and says, what’s the right translation? Or what’s a good translation to use, how do you answer that question? It’s a pretty popular question.

14:28

Dr. Ernst Wendland

This is one of the things that Gene nida taught me, and it comes out in theory and practice of translation, how to determine the right translation. I can’t do that as a consultant. It depends for whom is the translation intended.

14:42

Rich Rudowske

Okay.

14:42

Dr. Ernst Wendland

And you have to involve the target audience and get them involved. What type of translation do they want and what can best serve the community? I inherited two types of versions. In some cases a very literal early missionary version, and then a later dynamic equivalence version. And sometimes I had to prepare a new version. It was too dynamic. And sometimes you had to go for a toning down of some of the colloquial expressions and terminology to keep the current readership and churches happy.

15:16

Rich Rudowske

Okay, yeah, that makes sense. You have written suggesting that Bible translation be conducted using literary function equivalent style translating, or lifestyle translating. So what does that mean?

15:28

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Okay. It’s really not a new translation type. It’s an expanded version of the functional equivalence type of translation that aims to reproduce the functions of the biblical text using the closest literary oratorical forms of the target language. So that’s the key difference. The premise is that Bible is a literary collection of books. It’s not just a theological treatise. And we want to use the full resources of the receptor languages as much as we can to reproduce the impact and appeal, the rhetoric and the artistry of the biblical text to the extent that we can, in a modern translation, emphasizing the orality of the text, especially in Old Testament poetry, where we like the psalms, we’d like to reproduce that in a more dynamic, if you will, form that can be even sung if possible.

16:25

Rich Rudowske

Okay, let me ask first, in the english speaking world, with all the different translations, is there a Bible translation that manifests this approach in English?

16:33

Dr. Ernst Wendland

There’s no full Bible translation that does this. And why? Because it takes extra time to produce a life translation. And you have to have the translators with the gift. They have to be really poets orators in their mother tongue to do that. There is several versions. Brenda Berger of SIL has produced the poetic oracle english translation of the salter. That is what I would call a life version. Also, Timothy Wilt, a former UBS translation consultant, has published a number of books. For example, he calls it pigeon reference to Jonah in the Old Testament. So he has done a number. There’s several others. One, I forgot the name, the person who’s done the proverbs in a dynamic. So it’s individual books, mainly Old Testament, mainly poetic.

17:24

Speaker 5

Okay, sure.

17:25

Rich Rudowske

You mentioned that you can’t really determine what’s the best translation. The audience for whom it’s intended has to do that. So in your experience, how do you go about finding that out?

17:35

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Well, what I would try to do was to organize an initial workshop in the community and tried to get as many churches that were interested in the UBS works with all churches. And so the key was we would produce a version that would serve all the churches, Catholic and Protestant, so that we wouldn’t have two bibles. And so I would organize them, discuss the different versions. What was the problem with the old versions? Why do you want a new version? And what sort of. It was a matter of education. We’d have a week long seminar trying to explain the difference between a very literal version and a more functional equivalence, meaning oriented version. And try to give samples and see, in most cases, they already had an old version, so it was a matter of producing a new, more meaning based version.

18:25

Dr. Ernst Wendland

But the main thing was to try to get the churches involved. And what I tried to do was to, in the old days, everything was organized from Bible House, centrally located in Lusaka. I tried to organize local committees so that they would take more ownership of the project. So they set up their own administrative structure and everything that they would be involved in trying to source the translators, be responsible for supporting them, providing accommodation and housing and so forth, and to try to get that. Now, that often worked, but not often, always as well as I would have hoped, as of financial issues.

19:03

Rich Rudowske

Okay. Yeah. And I guess just listening to this idea of that, there were already translations. There’s one sort of, if I listen sometimes to the way that in the Bible translation movement, the need is expressed as here are all these languages without a Bible, and there’s a need to then make sure those all have one. And one could surmise, okay, once they have one, then that’s done. Right. But you would advocate that in a sense? Well, it’s never done. If I kind of take to the conclusion what you’re saying.

19:34

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Yeah, well, I would like to see, actually two types of translation, a more literal one to use perhaps in church, and a more meaning based one that people can understand. People, they confuse this. They feel that because the translation is literal, that it’s closer, that it’s a better translation. Yeah, but all you have to do to disprove that is ask them, what does it mean? I can take any passage at all in the old Chewa version that goes back to 1922 and ask people, what does this mean? What does this word mean? And the people can’t answer it. So you have a serious problem there.

20:04

Speaker 5

Sure.

20:04

Dr. Ernst Wendland

If we’re interested in true communication.

20:07

Rich Rudowske

Okay. All right. Sort of jumping off of that. Another area of study that I’ve read from you is frames of reference. And as an approach to translation, as an approach to ministry in general, really as an approach to just understanding what’s happening around you, I guess, would be a fair way to say it, but talk a little bit about frames of reference as an approach, what that is, and some of the practical implications of using that framework.

20:33

Dr. Ernst Wendland

It’s not necessarily a new translation theory or anything. It’s more involving cognitive linguistics a little bit in it. But it’s a polysystem methodology that seeks to explore the different interrelated aspects of a Bible translation process in a more systematic fashion with respect to not only the source language, but also especially the target language. We posit a series of frames, the cognitive frames, relating to the worldview issues of a culture, whether biblical or target language, sociocultural frames which relate to the distinctive aspects of the source or target language, background, social setting. And then the one thing that was brought out this morning, young lady came up and said, this organizational frame, we never even thought about that. What are the different organizations, religious or other, that play a role in a translation projects and the history of Bible translation?

21:33

Dr. Ernst Wendland

And then you have situational frames relating to the medium of communication, speech, acts and so forth, and zeroing in. Then finally on the textual frames, the biblical text itself, and normal exegetical analytical procedures.

21:47

Rich Rudowske

Yeah. So I think from a mythological perspective, thinking about things from that frame’s perspective is really important. Like you said, the young lady who mentioned the organizational frames, because there is the work of looking in the textual.

22:01

Speaker 5

But there is the whole strategy of.

22:03

Rich Rudowske

Looking at what sources or what situations are at play. I think of my own missionary experience and think how many times I approach the situation and say, okay, in this situation I’m approaching this as a Lutheran Bible translator’s missionary. But in this situation, I’m approaching the same basic thing as somebody who’s been seconded to work for the Bible Society of Botswana. And another time, I mean, I’ve been tasked to represent the Shikalahari speaking people of Botswana and know, in the same room, dealing with the same thing, but trying to think of it from all these different frames of reference. And then, I don’t know, the complexity of all the stakeholders in play, the churches, the organizations that are bringing things to bear. It really does.

22:49

Rich Rudowske

I think, in a way, at first it’s complicated, but it helps to clarify or at least get a situation on why is this so complex? Because there’s so many different things going on.

22:59

Dr. Ernst Wendland

It was interesting, one of my students at Stellenbush did a study of three different translations in Swana, the major language of.

23:07

Rich Rudowske

Yeah.

23:08

Dr. Ernst Wendland

And he explored that and tried to show, using the frames of reference, why these translations differ. And sometimes it was a worldview issue, sometimes it was organizational, a lot organizational, some relating to the current day situational factors.

23:23

Rich Rudowske

Right.

23:23

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Yeah.

23:24

Rich Rudowske

And then Tim Beckendorf. Do you know Tim Beckendorf by any.

23:27

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Never met.

23:27

Rich Rudowske

Okay, so he works in Botswana. He was on the podcast recently, and he got to, like, a specific frames of reference deal that he dealt with in his dissertation. But how the quaidam speaking people thought. They didn’t really have a way of talking about law and right and wrong and things like that until they thought of it from the frame of reference, of hunting and the order with which people can take and take things and not take things. The order, I don’t know if it taboos would be a correct way of saying it, but the point was they were able to finally derive from that there’s a reason that people do certain things in a certain way, and people then are allowed to do things and other people aren’t, so that ultimately everyone is protected and everyone is cared for.

24:13

Rich Rudowske

And moving from that frame of reference, then they could start to talk about God’s law and why God has a law in the first place. And I thought that was pretty fascinating. But really getting down to the textual part, where you start to look at frames of reference that way.

24:26

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Yeah, sort of following up on that. I think an important aspect of how do you determine the frames of reference for a target language today when nothing has been written? And that’s why I encourage translators and try to have a researcher, quote, unquote, on the team who would investigate the oral literature, what has been written in the language, so that when you come to a decision that has to be made, say, the name of God or Yahweh, can you justify, for example, the use of chauta for Yahweh? In Chichewa, it’s not Yahweh, it’s not Jehovah, it’s Chauta. It’s the high God of the Chewa people, the creator God. Now you have to do a lot of sort of cultural investigation in order to justify why we are using chaota instead of one of the loan words that are popular for that term.

25:14

Rich Rudowske

You mentioned 50 years in Zambia, so talk a little bit about how you have seen the church grow or change over the course of that time in Zambia.

25:24

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Yeah, well, it’s interesting factor. The Lutheran Church of Central Africa, LCCA consists of two synods, the Malawi synod and Zambia synod. They have grown since the 1960s, very rapidly, approaching probably some 50,000 members by the turn of the century. But since that time, the growth has leveled off, I think in competition to what we’re talking about this morning, the pressure from sort of the health and wealth pentecostal type of ministries. And so the growth has leveled off and has been a challenge again as the missionaries turned over the support of pastors to the national churches. So there is a challenge for adequate pastoral support. But on the other hand, at the teaching level, in both the LbI Lutheran Bible Institute in Malawi and the seminary in Zambia, they’re mainly all the teachers.

26:20

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Not all the teachers, but most of the teachers are mother tongue speakers.

26:24

Rich Rudowske

Yeah, I tell you what, I haven’t been to Malawi, but I’ve been to Zambia a few times and in several places there. And the one thing I can say about the LCCA pastors is every time I’ve attended a church and heard preaching and teaching, those are solid, well trained men that they know their stuff and they know how to communicate it winsomely and well, and they care for people, and that’s very impressive.

26:46

Dr. Ernst Wendland

It’s been a privilege to work with these men, I can say that.

26:50

Rich Rudowske

So you’ve worked as a seminary instructor and a Bible translator, then for decades, written voluminously about different ways of approaching the work and encouraging others and deep scholarship and so forth.

27:03

Speaker 5

But what does access to the Bible.

27:05

Rich Rudowske

Mean for you personally? When at the end of the day, you and your Bible, what does that mean for you? Why is that important to you?

27:13

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Well, the access of scripture, as a student of scripture, makes, on the one hand, the Greek and Hebrew available to me, then the mother tongue, of course, English. But then through the different languages that I have worked with, the Bantu languages, they have offered me diverse perspectives, I think, on the word of God that I would not have had otherwise. And so I thank the Lord for that opportunity. Things that I had never would have seen if I had looked at the biblical text only in English in my mother tongue. But being able to look at the source languages and especially in the different target languages that I worked with over the years, that has been a real blessing. Challenging on the one hand, but also made the scripture study fresh and interesting and inspiring for me through the days.

28:00

Dr. Ernst Wendland

And one never gets tired then of engaging with God’s word when you can learn new lessons every time and look at the different perspectives that the different versions make possible.

28:10

Rich Rudowske

Yeah. So what brings you joy in your work?

28:15

Dr. Ernst Wendland

I think over the years the greatest thing has been the opportunity to work with colleagues, national colleagues, in the work to, on the one hand, teach them, but on the other hand, to learn from them. I think every teacher has to be a learner. And I’ve learned so much from my seminary students and from my translation colleagues and the translators in the field. And as far as my translation staff goes, and also teaching staff, the greatest joy is to see some of the things that I’ve taught them, they are following up on, and now they are teaching me as they carry on the work in the different fields.

28:54

Rich Rudowske

So this is a question I ask on the podcast almost every guest, because I find that there’s just fascinating answers. So what do you think the western christian church can learn from the folks that you’ve been working with all these years? You name it.

29:07

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Okay. It’s a question it’s sort of hard to answer because I’ve been working with the african church all my life, and there might be a danger of me making a superficial comparison with the US church or western church. But I think the greatest thing that I’ve learned over the years is how the african church has been so open in welcoming me, a westerner, to work among and with them so many years and to teach me so many things. On the other hand, if we turned the tables and the scenario, how welcoming would westerners be to have an african teacher and evangelist be working among them? I think that’s a lesson interpersonal, interracial dynamics that the african church can teach westerners how open they were to me.

30:05

Dr. Ernst Wendland

But would the same thing be true if one of them tried to work in the United States, which is in some areas becoming very non christian?

30:14

Rich Rudowske

Yeah, that is an excellent question. I actually had a journal article I read where the Roman Catholic Church in the United States, due to priest shortage, has put in urban areas priests from Nigeria and dealing with the same.

30:28

Dr. Ernst Wendland

It’s happened in Europe too. England. I’ve heard.

30:30

Rich Rudowske

That’s fascinating. Yeah, that’s a great question. How can our listeners be praying for you and your family? I know this is an important time for you right now, so how can we pray for you?

30:42

Dr. Ernst Wendland

Well, I think Margie, my dear wife of 51 years, and I, I guess, would appreciate your prayers as we begin this transition and reentry into american life. It’s going to be rather strange and unsetling for us, I think, as we see how different the United States is from when we grow up. Grew up there and left the states in the 60s. She came to Sampia as a nurse in 69. Wow. And so we’ve never owned a home in the United States, and so that might be a bit of a challenge nowadays. But I think I would also welcome the prayers of listeners as I try to continue my teaching and translation ministry, working through schools like SATs, South African theological Seminary, working with doctoral students who want to work in Bible translation and need an advisor and an encourager along the way.

31:36

Dr. Ernst Wendland

We all would appreciate prayers to that end.

31:38

Rich Rudowske

Sure. Sounds great. Well, we are really thrilled that you were with us here at Concordia Mission Institute, and thank you for being on the podcast today, too, and sharing your perspective.

31:48

Speaker 5

It was great talking with you today.

31:50

Dr. Ernst Wendland

I appreciate the opportunity, a wonderful mission experience that I’ve had these few days. Thank you.

32:00

Rich Rudowske

Yeah.

32:01

Rich Rudowske

Reflecting on the interview with Dr. Wendland, I think the thing that is just hard for my mind to wrap around is the 50 years of ministry and all the changes and yet all of the trajectory and the work and thought that he has done and done with others that continues to build into this ongoing reformation continues, God’s word still going out to the ends of the earth and in new languages that began or found a catalyst at the time of Luther in the 500th translation.

32:31

Emily Wilson

Right. There is something, too of this is a prolonged process that when people are making a commitment to Bible translation, that it isn’t like a one off, like, okay, this is great. I’ll pray for you one day. This is an ongoing partnership, and when we call people into it as prayer partners, as financial supporters, as advocates for Bible translation, that people like Dr. Wenland are dedicating their lives to be able to serve with the goal of God’s word as the foundation for people to be able to have church and to grow and how powerful that is and transformative that is for the community.

33:17

Rich Rudowske

Yeah.

33:18

Rich Rudowske

And really, he was a pioneer, if you will, in this idea of the integral nature of. I’m here as a seminary instructor for a church. But Bible translation really has to be integral to that as well. And for the Wisconsin synod to give that latitude, for him to engage in both that seminary instructing and that Bible translation work, again, that’s the kind of stuff that Bible translation movement stuff is really exploring now, is how to be more integral in the church. And 50 years ago they’re already doing that there. And Zambia is a great example of how that has worked out and some of the innovation and the different styles of translation which are not an end to themselves.

34:02

Rich Rudowske

But really, if you will, it’s sort of a laboratory and looking at how to really work with the church and land on what the church really needs after several different approaches and articulations to land a I’m not sure how much that comes out in the interview, but all of the different styles and things we talked about and all these historical connections, they work themselves out practically in Zambia. And I do know when I’m talking with Dr. Wendland, before, he didn’t really want to get into all of the accolades that are personal accomplishments, because for him it wasn’t about that. It’s about God’s word in the hands of people.

34:41

Emily Wilson

And again, we want to encourage you, if you’re feeling pressed upon you, that you are wanting to join the Bible translation movement as a prayer or financial supporter, as an advocate, today’s your day. We are celebrating the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s New Testament into the vernacular German, and there’s no better time to be able to celebrate God’s word in the hands of his people. So join us at go lbt.org 500 to find out how you can join the Bible translation movement and celebrate Martin Luther’s 500th anniversary of the German New Testament.

35:22

Rich Rudowske

Thank you for listening to the essentially.

35:24

Speaker 5

Translatable podcast brought to you by Lutheran Bible translators. You can find past episodes of the podcast@lbt.org Slash podcast or subscribe on Audible, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. Follow Lutheran Bible translators’social media channels on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter. Or go to lbt.org to find out.

35:43

Rich Rudowske

How you can get involved in the.

35:44

Speaker 5

Bible translation movement and put God’s word in their hands. The essentially translatable podcast is produced and edited by Andrew Olson. Our executive producer is Emily Wilson. Podcast artwork was designed by Caleb Rodowald and Sarah Rudowski. Music written and performed by Rob Weit. I’m Rich Radowski. So long for now.

Highlights:

- “The opportunity to work with national colleagues — the work on one hand to teach them but on the other hand to learn from them. The greatest joy is to see some of the things that I taught them they are following up on it. Now they are teaching me as they carry on the work in the different fields.”

– Dr. Ernst R. Wendland - Dr. Wendland has over 50 years of missionary experience

- He encourages listeners to pray for his transition back to American life and continued work in translation